To put it bluntly, I’m extraordinarily disheartened by the failure of the grand jury in Ferguson to indict Darren Wilson for the shooting death of Michael Brown. The only thing that could be any more frustrating than the sheer will of the state not to prosecute Darren Wilson, is discovering that one’s allies aren’t all that invested, either.

Ferguson is about all of us, and Ferguson is about more than one incident. These are five reasons it’s well past time for feminists to pick up the Ferguson mantle.

1. Reproductive Justice is About the Right to Parent

My fight for reproductive freedom and bodily autonomy do not end at the point of childbirth, insemination, conception, or any point betwixt or between. I want reproductive freedom and bodily autonomy on demand, and without apology. Yes. Because of slavery in the United States (I refuse to apologize for invoking the legacy of terror that was American slavery), a tradition that extorted Black women’s bodies as breeders, “bellywarmers”, and objects of white male and female desire and derision, deciding to parent is just as revolutionary a choice as deciding not to.

Beyond slavery, we, as Americans, have an unfortunately rich rhetorical and cultural history of rendering Black women in the popular imagination as hypersexual, sexless, and/or emasculating beings, with little complexity beyond those strictures. Thanks to the collusion of racism, sexism, and classism, these unwarranted tropes even steer national policy, and serve as the subtext of laws that regulate the wombs of women of color. But Black and Brown women parent despite the affronts on their single parenting (think: Moynihan); despite the affronts on their parenting in the face of relationship violence outside of their home country (think: Congressional resistance to expand the 2013 provisions of the Violence Against Women Act); despite the affronts on their parenting while poor (think: “welfare queens”).

For these reasons, especially, it’s unthinkable that we would further encumber the parenting experiences of people of color. No parent should have their right to parent – their choice to parent – arbitrarily and unexpectedly interrupted or terminated because of state violence – violence that is all too often driven by the very same racist/sexist/Other-ist norms erected in the American subconscious. Lesley McSpadden and Michael Brown, Sr. did not deserve that.

2. Racism Is a Feminist Issue

She may not have intended to do so, but during some of the earliest battles for suffrage, Sojourner Truth is one of many Black women who reclaimed a space for Black women suffragists in the face of what could have been – and perhaps, would have been – the erasure of Black women’s fight for the vote and Black women’s fight for their own human rights in the 19th century. Truth declared, “And ain’t I a woman,” recognizing then that women’s fight to vote was not and should not be an inherently “white” enterprise, nor an essentialist one. Before the language existed, Truth applied an intersectional framework to call out the movement’s willingness to accept the investment of her labor, while at the same time brazenly disengaging the fight when the filter of race was applied. Plainly put, where the women’s movement was concerned, Truth called out their white privilege, and at the same time refined the argument for a sex-conscientious revision to the standing laws of the land.

Whether we care to admit it or not, the undercurrent of race in the Ferguson proceedings actually serve to remind us just how intrinsically tied race has been to the evolution of feminist theorizing.

Unfortunately, it’s because of the legacy of institutionalized racism that the demographic and political dynamics of Ferguson, Missouri can be replicated all over the country. Likewise, in contemporary feminist fights to raise the minimum wage or stop the evisceration of abortion clinics by TRAP laws (Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers) around the country, without fail, the narrative devastates women of color and low-income women the most. The substance of the feminist movement is amplified by the experiences of these women, precisely because of intersectionality – an inherently revolutionary feminist principle attributed to Kimberlé Crenshaw.

That said, it would behoove us all to put our intersectional and critical analysis to work here in the case of the Ferguson grand jury decision, the issue of excessive force, and the international movement that declares Black and Brown lives matter.

3. Fighting State-Sanctioned Violence is Part of Feminist Herstory

Around this time of year in 1917, the Silent Sentinels, a group of women who adamantly fought for women’s right to vote, held a pop-up protest of President Woodrow Wilson. Please note, this bastion of women’s suffragists “illegally” chained themselves to the White House gates and obstructed traffic. On this occasion, they endured attacks from angry mobs who disagreed with their fight, yet the women were arrested and tortured while their attackers went free.

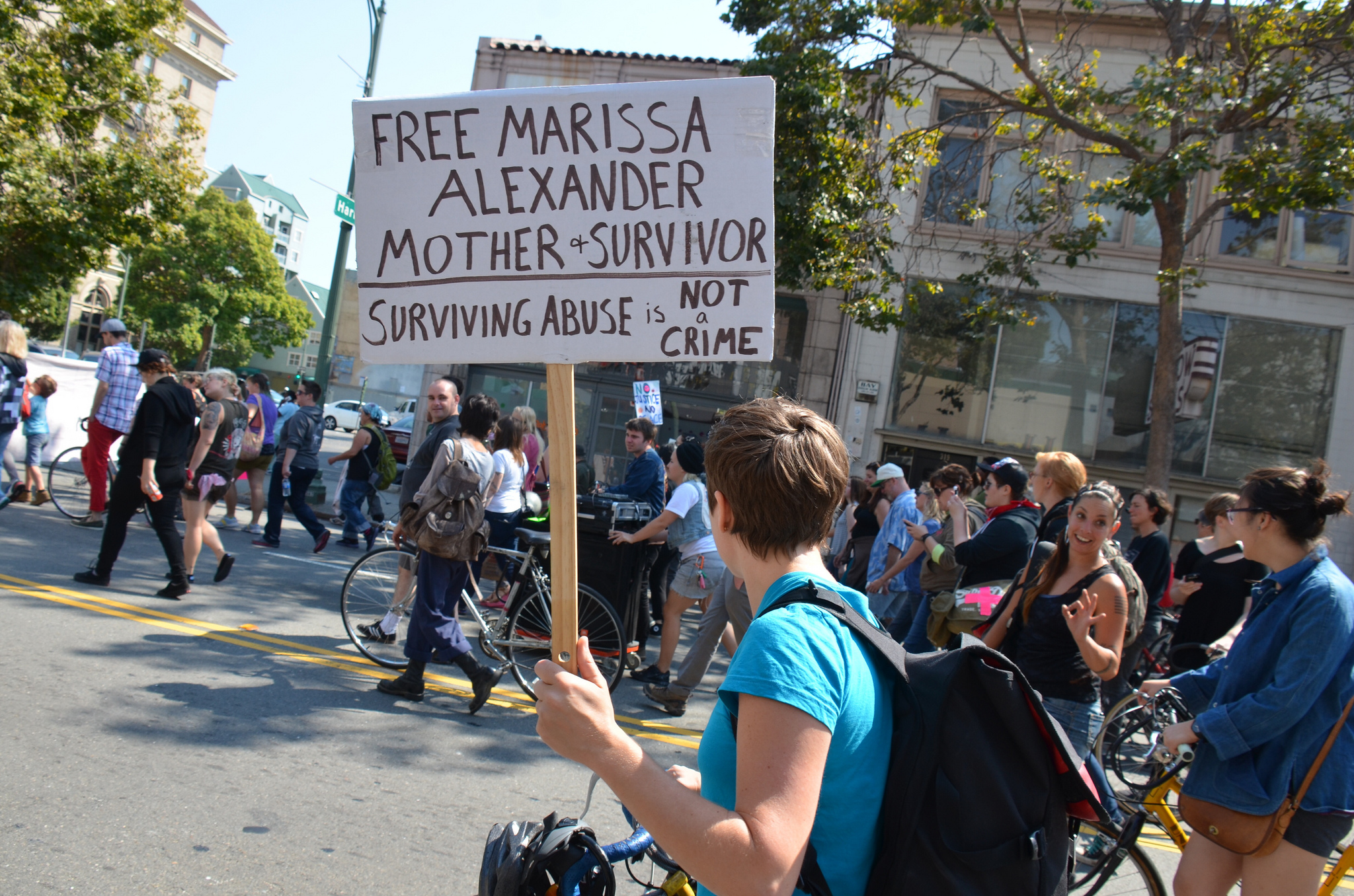

Not only could and should the Silent Sentinels serve as a springboard for robust feminist dialogue and organizing around the contemporary fight to end mass incarceration and reform the American prison system, but it should serve as a case study in state violence.

State violence is what’s happening right now in Ferguson and across the country. State violence favors “Otherness”, and it is altogether rabid when the object of that violence is a Black or Brown body. The notion that being an officer imbues impunity under the law is of tantamount importance in understanding why ongoing demonstrations across the country and around the world have been fueled by the grand jury’s no-indictment decision. This is why I’m blocking roads and disrupting business as usual.

First: I’m not hard to find. St. Louis. North side. Second: Nappy? pic.twitter.com/UDVEC3MNrB

— Antonio French (@AntonioFrench) December 2, 2014

Yet, vigilante elements like the Oath Keepers and the Ku Klux Klan, have emerged to capitalize on racial tensions under the guise of keeping peace. That their physical presence can go unchallenged, while the threat of protesters’ rage precipitates the declaration of a state emergency is concerning. In fact, it represents a rhetorical form of state violence.

Fellow feminists, dig out the parallels in this fight.

4. Justifying Police Brutality Sounds A Lot Like Victim-Blaming

“What were you wearing?” “What did you say to offend them?” “Why were you alone? Why were you in the wrong place at the wrong time?” “You should have known better…” “Why didn’t you fight back/defend yourself/surrender?”

Just as we would discourage the re-victimization of a sexual assault survivor, we must be willing to resist blaming those who have been victims of police and state violence.

Tamir Rice was 12 years old at the time of his two-second murder by Cleveland police just weeks ago. That did not preclude his second death-by-media in the afterlife. Tamir’s “behavior” – and subsequent death – were blamed on his father’s history of domestic abuse, and his mother’s drug problem. Tamir, a sixth-grader, apparently looked like he was 20. Race and gender again collude to undermine our recognition of Tamir as a victim. Instead, this Black male child’s murder is not only justified, but further, charged to his own indiscretions, which are all the more provocative because of how we render Black masculinity, no matter what age.

Immediately following the death of Michael Brown, the hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown emerged to illustrate just how race filters our understanding of “true” victims.

Under the right circumstances, feminists call that “slut-shaming.” Let’s not forget our principles now.

5. Women Die from Police Violence, Too

Women are victims of excessive and lethal force, too. Know their names.

Rekia Boyd, 22, deceased. Tarika Wilson, 26, deceased. Aiyana Stanley-Jones, 7, deceased. Miriam Carey, 34, deceased. Yvette Smith, 47, deceased. Tyisha Miller, 19, deceased. Sharmel Edwards, 49, deceased. Shantel Davis, 23, deceased. Shereese Francis, 30, deceased. Pearlie Golden, 93, deceased. Maria Godinez, 22, deceased. Kathryn Johnston, 92, deceased. Gabriella Navarez, 22, deceased. Eleanor Bumpers, 66, deceased. Tanisha Anderson, 37, deceased. Aura Rosser, 40, deceased. Karen Cifuentes, 19, deceased. Yanira Serrano-Garcia, 18, deceased. Marlene Pinnock, 51, beaten. Sandra Amezquita, 44, pregnant, beaten. Denise Stewart, 48, dragged naked from home. Brenda Hardaway, 21, pregnant, beaten. Mayra Lazos-Guerrero, 25, pregnant, intentionally tripped by officer. The 13 sex assault victims of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, youngest age 17. Cleveland, Ohio 15-year-old, sexually assaulted on video by an officer. Florida 20-year-old raped by a Boynton Beach police officer.

This list doesn’t begin to account for the gravity of the problem, but it certainly deserves your energy, your feminist engagement, and even your outrage.

We can’t deny it, we can’t talk around it. Ferguson is a feminist issue. Tell me in the comments, fellow feminists: why is this fight your fight?